Twenty-two years after a British military intervention and six and a half years after the containment of Ebola, a dangerous new political game could be about to hamper Sierra Leone’s regeneration.

In a seemingly progressive move, newly elected President Julius Maada Bio, has pledged to roll out free quality education for all. There are, however, questions about the legitimacy of the pledge and the government’s ability to implement such a change.

An ambitious free education programme has yet to be successfully rolled out in a conflict-stricken African nation. Should it backfire, it could drive away education-focused foreign aid – aid upon which the children of Sierra Leone have long depended.

Western charities are now challenged with delivering a nuanced and confused message: fundraising for schools in a nation that promises free education. A case in point is the Menina School, which was established in 1985 and supports three surrounding villages. The school, which withstood the 1991–2002 civil war, is struggling having lost its funding under President Bio’s Free Quality School Education (FQSE) programme.

“We have not yet received any approval from the government,” said Ibrahim Jamikki, headteacher at the Menina School, Kenema District.

“For a few years, we are receiving a subsidy. As soon as the new government has taken place – we are yet to receive anything.”

The headteacher is one of the many volunteers working in the education sector whose schools have lost funding under the new government initiative – as a number of rural schools throughout the chiefdoms are yet to be included in the programme, causing a great deal of resentment.

“Only one hundred schools have been approved across the nation,” said Sarah Reed, a campaign manager for the education-focused charity Street Child. This has left hundreds of existing schools awaiting approval and thousands of children without textbooks, uniforms and other materials.

Reed, who welcomes Bio’s ambitions, is concerned that the pledge could drive away funding from Street Child.

“When Street Child’s work began in 2008, Sierra Leone was the poorest nation in the world… We’ve since supported over 12,000 families and helped over 22,000 children to go to school.”

Failure of the FSQE program to deliver throughout Sierra Leone’s chiefdoms could exacerbate the skills and literacy gap between rural and urban areas. It’s unlikely to reignite the tribal hostilities that Bio fought to ease in 1992, but could hamper the programme’s ambition to regenerate the nation as a whole.

An article by the Sierra Express Media echoes Jamikki’s frustration, comparing current efforts with that of the previous government.

The report suggests that although there is support for free education, school materials were cheaper prior to FQSE and that ‘things are getting tougher’.

The article denounces the FQSE programme as a vanity project – suggesting it’s designed only to promote the nation on the world stage.

‘Sierra Leoneans are sending this strong message to both their past and present leaders to stop telling the world that the country is leading [sic] to prosperity while her people are dying of hunger’.

The government’s gambit has seen big political promises rub up against the realities of provision. Teachers and the communities they serve have been left waiting – dependent on foreign aid to support schools located outside the cities.

The redistribution of subsidies has resulted in teachers working voluntarily, taking on second jobs, and source learning materials, such as chalk, themselves. While it’s not unusual for teachers in developed countries to spend their own money on classroom provisions, such altruism is all the more note-worth in an impoverished country like Sierra Leone.

President Bio rose to political prominence in 1992. He was one of 30 armed military men who drove from Sierra Leone’s warring front to the capital, Freetown. There they peacefully overthrew the corrupt and repressive single-party dictatorship which had ruled over the country for twenty-five years.

Talking at a TED conference in 2019, Bio stressed that he entered government with the sole aim of restoring democratic rule. Having waited four years, Bio became frustrated at the lack of elections, and in 1996 staged another bloodless coup, this time instating himself as head of state.

With millions of Sierra Leoneans already displaced by tribal conflicts, Bio embarked on a political mission to persuade remote rebel leaders to engage in peace talks. He encouraged them to look beyond their differences and engage with the wider needs of Sierra Leone.

These talks were deemed a success and Bio implemented the first democratic elections in nearly thirty years. He handed power to the newly elected president, resigned from the army and left the country to live and study in the United States.

After a violent and politically turbulent twenty years, Bio returned to Sierra Leone and was subsequently democratically elected president. A proponent of universal opportunity, Bio had one key electoral pledge – if elected, he would prioritise the development of human capital through education and skills training provision for vulnerable Sierra Leoneans.

He cited education in particular as the key to overcoming the challenges facing Sierra Leone.

“The secret to economic development is in nature’s best resource, skilled, healthy and productive human beings.”

Addressing the nation’s cycle of dependency and economic instability, he added: “We have mined mineral resources for over a hundred years … We have collected foreign aid for 58 years, but we are still poor.”

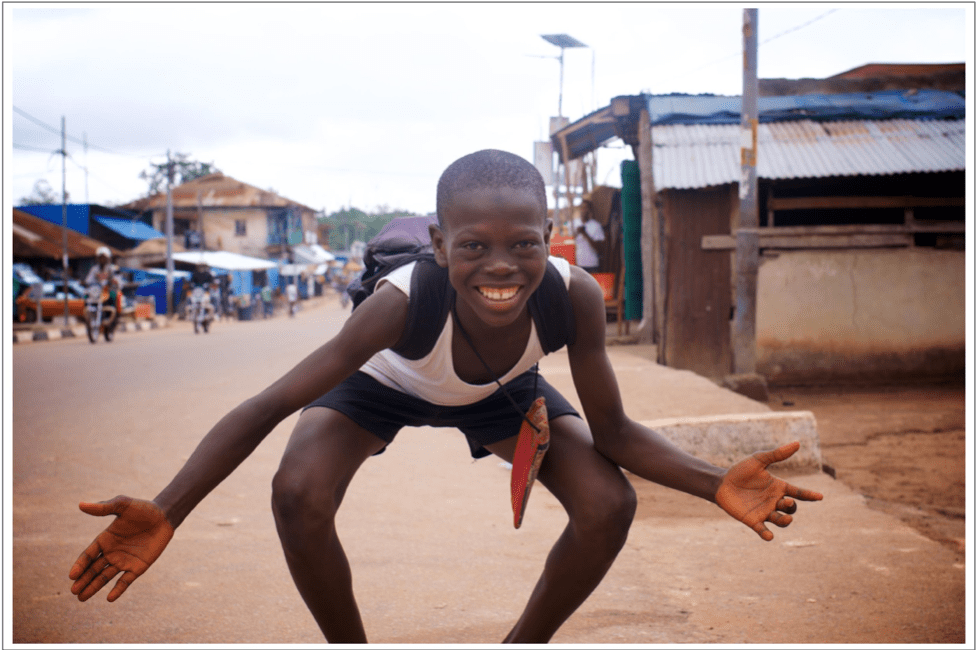

The people of Sierra Leone are an ostensibly resourceful and industrious people, women walk the roadsides balancing everything from washing soap to fruit on their heads – men huddle in shacks welding scrap metal into functional everyday objects. Trucks carrying iron ore roar past regularly and the once bloody diamond trade is becoming increasingly mechanised and legitimised. Pineapples, mangoes and coconuts grow in abundance, and the white-sanded beaches are a breathtaking reminder of the tourism industry of the 1970s.

Despite such economic promise and a myriad of resources, the nation is yet to harness its assets to transform itself into a sustainable developed country. According to the 2019 UNDP Human Development Report, Sierra Leone remains 181st in a multidimensional poverty index of 189 countries .

The median age in Sierra Leone is 18.5 years old. The country has the seventh-lowest life expectancy and one of the highest rates of infant mortality in the world. In addition to Ebola, malaria and HIV, the medical community has expressed concern that diabetes is rapidly becoming a national health emergency, an emergency that the nation is ill-equipped to treat.

A lack of public awareness of tropical hygiene, water management and sanitation has exacerbated the spread of hepatitis A and typhoid. The government doesn’t have the resources to maintain and distribute clean water, though with the correct guidance, the people of Sierra Leone could learn to treat contaminated water to minimise health risks.

Inside the classroom, policymakers are focused on addressing child illiteracy. A government census conducted in 2015 defined illiteracy as the inability to read or write a simple sentence in any language. The same paper showed that just under half of all Sierra Leoneans were illiterate. The percentage is significantly higher in rural areas, with more than three in five deemed illiterate, compared with three in ten in urban areas.

Though English remains the official language of Sierra Leone and is spoken throughout the country, people in remote rural areas are more likely to adopt regional dialects such as Mende, Temne, Limba and Krio.

Many of the country’s most remote schools are accessible only by boat or jungle track.

Headmaster Sorie Conteh makes the treacherous journey to the Kabba Ferry School in the Upper Tambakha District five days a week.

“I live in Kabba Ferry, over the river. Every day I travel three kilometres coming, three kilometres going. That is six kilometres, going and coming,” said the teacher.

Conteh, who volunteers at the school, spends his weekend labouring on a farm to support his family while the school awaits FSQE approval.

Whilst failing to support the farthest reaches of Sierra Leone, the FQSE program has seen some modest success in and around urban areas. Since August 2018 the programme has circulated more than twelve million exercise books to government-approved schools. Subsidies have contributed towards furniture, training, salaries, sanitation and structural enhancements. Parents and guardians who send their children to an approved school are no longer burdened with a $20 annual school fee.

Bio’s commitment to education is without question, devoting 21% of the national budget to FQSE.

He talks with bombast and enthusiasm about, what he calls his “daring” plan.

“But of course we can’t afford any of this,” the President jokingly remarked at the recent TED conference.

Unfortunately, there may be some truth to Bio’s joke. Free education is an ambitious goal, especially for a nation with Sierra Leone’s burdens.

Should Bio’s high stakes gamble pay off, however, he would be championed for achieving the unachievable, creating a blueprint for post-conflict reconciliation. Namely, reshaping the expenditure paradox faced by war-torn countries, and demonstrating how free education can encourage foreign investment and improve health care.

Failure, one the other hand, could drive away foreign aid and lose Bio the confidence of the electorate, exacerbating Sierra Leone’s cycle of poverty, disease and desperation.

Specific names have been changed in this article at the resquest of Street Child UK